Film programme

The EMAF screens experimental and artists’ films from around the world and is interested in forms that move along disciplinary peripheries or between film and performance, document and experiment. Short and long, digital and analogue films that relate to social and political reality in an exploratory and questioning way find their place here. At the same time, the EMAF is open to works that test new forms of cinematic presentation. Our aim is to make cinema a space for encounter and exchange: a space for projections beyond the status quo.

The EMAF film programmes are developed in collaboration with international curators, artists and theorists who, as members of the selection committee, select the contributions for competition- and feature-film programmes, or are invited to develop their own thematic programmes and series.

Three prizes will be awarded as part of the competition: the EMAF Award, the Dialogue Prize and the EMAF Media Art Prize of the Association of German Film Critics.

Awards and Jury Statements

EMAF AWARD

Emily Wardill, Night for Day

The EMAF prize is awarded to a poignant work that explores the power of cinema as a tool to time travel, and to create imaginary kinship across generations. Emily Wardill’s Night for Day is a haunting film that enfolds a myriad of narrative strands to unpack the dialectics of utopian thinking, and the concrete realities during and in the aftermath of a revolution. Almost as a counterpoint to the precision afforded by current image technology, Wardill expertly employs light and shadow as a filmic device that points to the opaque and fractal nature of historic narratives as well as present realities. She integrates excerpts from a fictional diary, glitchy footage of films and recorded theatre performances dealing with (mostly female) automatons to create sometimes harsh breaks within the narrative fabric and to work against the illusionary pull her own images possess. Through the film’s constructed mother-son relationship, Wardill questions the notion of commonality as visions of a past political utopia and the present technological utopia come into dialogue in these discordant times.

Special mention

Simon Liu, Happy Valley

Several of the films in this year’s program contend with stories of political struggle, and the jury would like to give special mention to Simon Liu’s Happy Valley for its heartfelt portrayal of the beauty of everyday life in his home city, after the 2019 protests. What happens to a city after such an intense collective experience? What remains? and mostly how does one create new experiences when any sense of ‘normal’ is impossible to get back to? A collage of surreal and material observations of the city, set against a soundscape of 80s Hong Kong pop songs and soap operas, it evokes a deep sense of longing for a common experience, and is a celebration of a survival instinct that is fundamentally human and universal.

Dialog Award

Ana Vaz, Vera Amaral, Mário Neto, 13 Ways of Looking at a Blackbird

The winner of the Dialogue award is a work which circles around the camaraderie between a teacher and her students. Centered on Wallace Stevens poem 13 Ways of Looking at a Blackbird, the collaborative film traces their journey in locating themselves in the world. Comprised of a series of inquiries, the film is a remarkable exercise in unschooling founded upon intergenerational rapport and curiosity, where they jointly explore ways of seeing beyond sight. By doing so, filmmaking becomes a performative and sensory practice that involves the entire body. The film’s evocative soundscape and use of multi-vocality adds to the layered texture of the film that is underpinned by the present discourses of care and generosity, as we witness these young filmmakers investigate the relations between the visible and invisible, the sensible and insensible facts that will constitute how they view the world.

Special mention

Suneil Sanzgiri, Letter From Your Far-Off Country

The jury would like to give special a special mention within the section of the Dialogue award to a work that evokes the power of communication through letters that connects the protagonists of emancipatory struggles in India through almost half a century. In Letter From Your Far-Off Country Suneil Sanzgiri explores how historic events can be turned into performative gestures which then inform present and future tactics in fighting oppression and censorship. He follows the images and sounds of revolutionary moments by bringing different sources such as analogue video, 16mm footage and digital renderings together thereby not only destabilizing a linear historic narration but also blurring the boundaries of experimentation in cinema.

Media Art Award of the German Filmcritics (VDFK)

Marian Mayland, Michael Ironside and I

Abandoned spaces of adolescence in films and series from the previous century. The light is still on, technical devices switched on, control lamps flashing, PC keyboards are waiting for input. The protagonists are missing. A narrator has investigated what has become of them since they left these film spaces. From the present off-screen, he speaks of sexual assaults, career endings and a suicide. His own youthful enthusiasm, on the other hand, has encapsulated itself in the inanimate, technoid facilities. A new space is discovered, a door opens – into a space that is also just a film space. Coming of Age as Coming of Film misfires.

The VdFk jury commends a complex essayistic examination of film and television history. In the flowing montage of found genre images, traces of toxic masculinity become visible that do not permit nostalgic transfiguration. Nonetheless, the author’s cinephile sensitivity remains the fuel of (self-)reflection.

The EMAF Media Art Award of the German Film Critics is given to Michael Ironside and I by Marian Mayland.

Competition

From over 2600 submissions 31 films were selected for the International Competition. They are as diverse in content as they are formally independent, and yet reveal some common issues and thematic focuses. Thus, a number of films deal with places and landscapes marked by the traces of historical events or current conflicts and undertake a critical or personal stock-taking. At the same time, they express the desire for alternatives: the question of other world models and new forms of living together, which is answered with the creation of utopian universes or recourse to traditional cosmologies and indigenous knowledge.

Sharing and passing on experience, learning and understanding across cultural borders and geographical distances is also a key focus. This involves individual acts of speaking, silence or concealment, the political dimension of witnessing and remembering, or the empowering potential of translations. Other works revolve around the close connection between body, place and identity. They play with the medial production and subversion of gender concepts, find idiosyncratic formal strategies to deal with experiences of discrimination and violence, or tell of the contradictory longing for bonding and dissolution of boundaries.

Feature Films

The four feature-length films in the programme find a language that is as critical as it is humorous to illuminate the often-silenced connections between social class and artistic career, or use documentary, fictional and performative forms of cinematic narration to tell the story of a black commune in the USA. The portrait of an early women’s rights activist and socialist finds an unconventional form to honour the linguistic power of this historical figure, while a feminist film classic of the 1990s both cleverly and subversively focuses on a subject that film history has virtually ignored: menopause.

The Unpossessable Possessor

Curated by Anja Dornieden and Juan David González Monroy

“The gods have become our diseases.” C. G. Jung

In his essay “For a Metahistory of Film: Commonplace Notes and Hypotheses”, Hollis Frampton posits the idea of the “Last Machine”. He describes this machine as made up of “the sum of all film, all projectors and all cameras” and calls it “the largest and most ambitious single artifact yet conceived and made by man (with the exception of the human species itself.)” 1

His description of this machine continues by following a consistent, if gruesome logic: “It is not surprising that something so large could utterly engulf and digest the whole substance of the Age of Machines (machines and all) and finally supplant the entirety with its illusory flesh. Having devoured all else, the film machine is the lone survivor.“ 2

In the service of this machine – according to Frampton – we are “doomed to the comically convergent task of dismantling the universe and fabricating from its stuff an artifact called The Universe”, of which its ultimate manifestation is “an endless film archive built to house, in eternal cold storage, the infinite film.” 3

If devouring the universe and enslaving us into its eternal reconstruction is the film machine’s logical end point, we have to ask ourselves: Why did we allow it to exist in the first place? And perhaps more importantly: Why do we continue to be its willing assistants?

Now, it can be seen as the ultimate act of human self-regard and hubris to anthropomorphize non-human creatures and inanimate objects. But perhaps we don’t anthropomorphize enough. Perhaps, in order to understand how we got to this point and to grasp where we might be headed, we have to accept that the film machine is not just humanlike – possessor of human traits, emotions and motivations – but too human, absurdly human, oozing humanness.

Were we to add to Frampton’s diagnosis, we would suggest the following profile for the current incarnation of the film machine:

“Superficial charm and good intelligence; absence of delusions or other signs of irrational thinking; absence of “nervousness” or psychoneurotic manifestations; unreliability; untruthfulness and insincerity; lack of remorse or shame; inadequately motivated antisocial behavior, poor judgement and failure to learn from experience; pathologic egocentricity and incapacity for love; general poverty of major affective reactions; specific loss of insight; unresponsiveness in general interpersonal relations; fantastic and uninviting behavior with drink and sometimes without; suicide rarely carried out; sex life impersonal, trivial and poorly integrated; and failure to follow any life plan.” 4

At the same time, the film machine hides much of this behaviour behind a mask of charisma and leadership. It presents an attitude of comfort and nonchalance, which make it seem like following its whims is a viable alternative to the droning reality of everyday life.

Which is to say that the film machine displays the attributes of a psychopathic personality. Of course, the machine is not solely to blame for its character. Clearly, we created it in our image. It would not be going too far to call it our child. But its aberrant behaviour points to some deficiency in the relationship. Something in its upbringing has certainly taken a wrong turn.

It would be easy to fall into despair at our missteps as parents. The film machine’s antisocial and sociopathic behaviour can lead to deep feelings of personal failure and guilt. Nonetheless, it’s true that “the nuclear family is usually the easiest group for the adolescent or adult sociopath to manipulate.” 5

Motivated by our parental concerns, and specially our guilt and protectiveness, the film machine has taken advantage of a dynamic where, no matter its irresponsibility and the damage it causes, we continue to offer our help and support. And so, by persisting in our attempts to bail it out of trouble and fruitlessly undo its wrongs, we place ourselves on the path of unceasing suffering. As Frampton’s eternally cold archive/prison should make clear, continued reinforcement is very costly.

Simply ostracising the film machine though, is not a realistic option. There is little chance that we will simply turn the machine off and go on with our merry lives. Not just because banishing your offspring is a choice few are willing to make. The interdependence of our relationship is enrooted at a more elemental level. Allowing ourselves for a moment to jump metaphors and skip from the filial to the ecological, our dynamic can be further seen as one in which we are caught in a process of coevolution with the film machine. As it has been growing, mutating and evolving, the film machine has been forcing pressures upon us that have obliged us to change and evolve in response. We’ve naively laboured under the impression that we created and have been shaping the machine for our own pleasure when, in reality, it has equally been modifying us for its own needs. 6

So, we find ourselves at an impasse: we cannot break up with the machine (it would never let us, and we would never want to anyways) and it certainly cannot leave us (who would feed it its images). Which means that we carry on, stuck with each other; adding to the pile of so-called “content” as the mangled monstrosity that is the infinite film continues its slow lurch of blind expansion. 7

To even begin to find a way out of our predicament, we need a better picture of the film machine’s nature. This image is not only for our benefit (although that is also long overdue) but is in fact most useful for the film machine itself. For the machine’s appetite – its need to consume the whole of reality – imposes upon it a drive for completeness that the infinity of its hunger makes by design impossible to satisfy. Its knowledge, however unconscious, that it will never be full, is the source of its ever-present anxiety.

And so it struggles for coherence where none exists. It uses a multitude of dishonesties and delusions to hold itself together; a way to walk the narrow path on the cliff’s edge, ever fearful of falling into the abyss.

It’s quite unlikely that we will be able to make the film machine change its ways by force but there might be a way to trick the machine into surrendering its unbearable drive. Every film screening is an occasion for the film machine to re-enact its narcissism but perhaps these occasions can be used as an opportunity to hold a mirror up to the film machine so that it can face its self-centred ways.

In order to achieve this, we have chosen to cut out and examine small sections out of the incoherent aberration that is the infinite film. We hope that these samples will offer the machine a true reflection of its distorted self; an image of what the machine has done to itself – the endless mutilations – in order to exist at all. Our hope is that this encounter will force the film machine to confront the absurd reality of its outward presentation and thus, come to terms with the futility of its desire.

To see and to know this image might just be a way for the machine to realise that, no matter its effort, what it has amassed, in the end, is nothing. It has nothing and therefore is nothing. To see and to know will reveal that it can never see and know (for there is nothing to see and know) and as it floats in the void that is its self it can finally sleep and for the first time, dream.

1 Hollis Frampton, On the camera Arts and Consecutive Matters, The Writings of Hollis Frampton, ed. Bruce Jenkins, (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2009), 137.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 List of symptoms taken from Hervey Cleckley, The Mask of Sanity, (St. Louis: C.V. Mosby Co., 1976), quoted in Lois A. Leaff, M.D., “The Antisocial Personality: Psychodynamic Implications.” In The Psychopath: A Comprehensive Study of Antisocial Disorders and Behaviors, ed. William H. Reid, M.D., M.P.H., (New York: Brunner/Mazel, 1978), 80.

5 William H. Reid, M.D., M.P.H., “The Sadness of the Psychopath.” In The Psychopath, 12.

6 Host-parasite is a common form of coevolutionary relationship. However, trying to determine who is the host and the parasite in the case of the human-film machine interaction opens up avenues of thought dealing with power and pleasure that, reasonably explored, would exceed the confines of this introduction. Nonetheless, any further research might be helped by perceiving these positions not as static identities but as interchangeable parts in a couple’s roleplaying games (and here once again our metaphor keeps leaping away from us and toward the realm of the sensual, where perhaps any further investigations of the film machine belong.)

7 That such as vapid word as “content” has become the source of so much discomfort among some members of the cognoscenti speaks to the psychological weight of the mountain of unwieldy slop that we continue to serve up for the machine to ingest.

References and Appropriations

- Frampton, Hollis, On the Camera Arts and Consecutive Matters, The Writings of Hollis Frampton, edited by Bruce Jenkins, Cambridge M.A.: MIT Press, 2009.

- Jung, C. G., Alchemical Studies, Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Volume 13, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1968.

- Reid M.D., M.P.H., William H. (ed.), The Psychopath: A Comprehensive Study of Antisocial Disorders and Behaviors, New York: Brunner/Mazel, 1978.

- Shipley, Gary J., “Dreaming Death: The Onanistic and Self-Annihilative Principles of Love in Fernando Pessoa’s Book of Disquiet”, Glossator: Practice and Theory of the Commentary, Volume 5: On the Love of Commentary (2011): 107-138, https://solutioperfecta.files.wordpress.com/2011/10/g5-gs3.pdf

- Thewlis, M.D., Malford W. and, Isabelle Clark Swezy, Handwriting and the Emotions, New York: American Graphological Society, Inc., 1954.

Show Us the Money and We Will Resist

Curated by Nour Ouayda

“The first image is always a surprise”, says a voice-over in Akram Zaatari’s video Countdown. This video is part of a series called Image + Sound that edits TV news footage alongside staged events. It aired on the Lebanese Future TV in the mid-90s as part of the morning show Aalam al Sabah. How did such an experiment in form end up on Saturday morning TV in 1995? “You need to shock the viewers,” says Fouad Naïm, director of TéléLiban between 1993 and 1996, when asked why he would program a show as experimental as Mohamed Soueid’s Being Camelia on public television. The first image is always a surprise but, past that initial encounter, the second, the third, and all the images that come after are less of a shock as they make way to showing the viewers that “there exists an alphabet other than the one they are used to”, Naïm explains. The 1990s in Lebanon were marked by efforts of reconstruction of the capital and the country following a general amnesty law that ended the civil war without any reparations. It was within this context that a restructuring of the television sector took place with the government reducing the fifty existing channels (each political party and militia had its own broadcasting channel) to around ten. Channels such as TéléLiban, a public television network owned by the Lebanese government, and the newly founded private Future TV recruited young talents and gave them access to professional equipment and airtime. This led to the unusual (and never-since repeated) freedom to produce various video experiments on TV, marking the beginning of the careers of filmmakers such as Mohamed Soueid and Akram Zaatari. Today, the use of social media and online platforms by institutions and initiatives as space to commission works creates a similar structure of production, allowing for and stimulating experimental film gestures that cannot find a place in the more normative residency-grant-festival-circuit. This recourse to social media, and especially a platform such as Instagram, has gained more importance since the beginning of the pandemic. Structures such as the Beirut Art Center have been using these platforms to host their online micro-commissions while Rehla, an underground experimental magazine, uses it to publish found footage mashups that relate to a monthly theme explored in each issue. We also see filmmakers and video artists using these platforms as an extension to their work and research such as Chantal Partamian’s Katsakh account in which she explores various analogue film processes through short capsules that allow us to peek into her experimental film practice. Zaatari describes his videos from the time he worked at Future TV as “moments stolen from television and not produced by television.” The freedom to experiment is not only one that is granted but one that is taken and reclaimed in order to hijack and subvert a certain production apparatus. “Let’s raid the television”, Fouad Naïm and Mohamed Soueid used to say. Echoing two distinct moments in time (Lebanon of the mid-1990s and today), the works in this program unfold various unexpected gestures in film and video experimentation that act as small beacons of resistance, showing that different modes of production are always still possible. So: Show us the money, give us access to the infrastructures, and we will resist.

The New Death

Curated by Jaakko Pallasvuo and Steve Reinke

It is too late, epoch-wise, to have thought of this now, but it seems to me we’ve been using the wrong model for anxiety. Instead of looking into the void and finding the void looking back at you (Nietzsche) it should have been sticking your finger into the world and, when you bring it back in to yourself, smelling nothing (Kierkegaard).

He pulled my finger and nothing escaped as a gas. It was nothing to point out, no specific thing, just a small cloud of the nothing that upheld the world. The finger was also nothing.

Media art on the other hand was everything. Even if it mostly recorded sound and vision, not smell.

When I got stung by a jellyfish, I felt like we were really communicating. The jellyfish did not have fingers, hands, arms, eyes, a heart or a brain, but its message was effective and hard to ignore.

The Anthropocene continues apace and the bodies pile up — not only the extinction of species (many of which were annoying anyway) but the eradication of entire genera (most of which must contain something of value). Families, orders, classes, phyla — even the kingdoms will crumble. This changes death. Here is work that heralds, discusses, celebrates the new death, this fresh death.

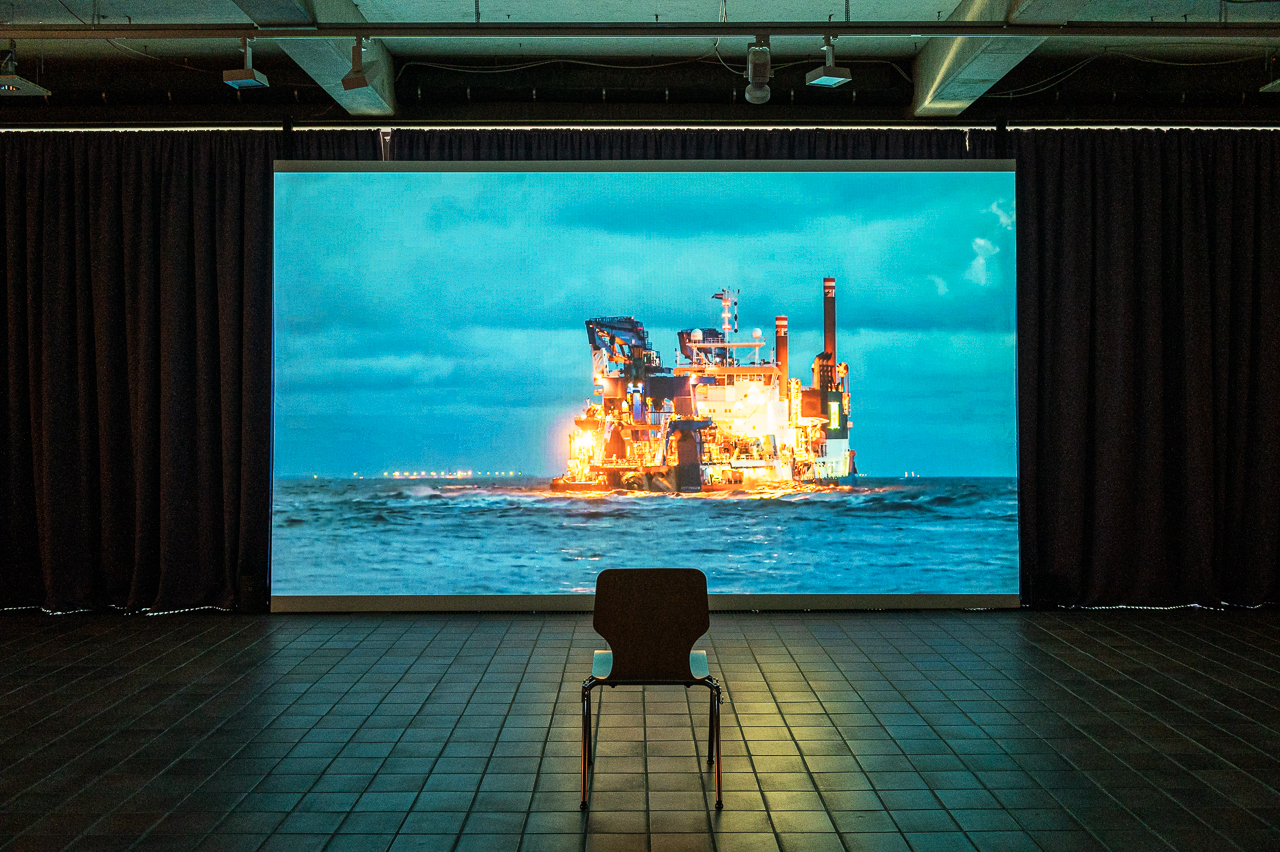

Exhibition

The exhibition takes the festival theme “Possessed” as its starting point and explores the meanings of possession and obsession in relation to old and new forms of extractivism and colonialism with its racist regimen of ownership. The collected works thus deal with the appropriation and exploitation of land, natural resources, data, identities, cultural heritage and history, and expose their consequences for societies and nature, for the body and the psyche. They interrogate the human obsession with profit maximisation, progress and global fantasies of technologically controlled, frictionless living. The resulting injustices and traumas continue to have impacts to this day, while the violent extractive practices of historical colonisation combined with the abstract quantification methods of new technologies are ceaselessly evolving.

What roles do technology, connectivity and networked infrastructures play in new forms of ownership and dispossession? What might a model of civilisation look like that is not based on unlimited growth and unbridled exploitation and subjugation of nature? In what ways do rituals and beliefs shape our understanding of property, or can change it?

The artists use large-scale installations, documentary film, machine learning and the tools of counter-cartography and data visualisation to confront these questions. They use practices of storytelling, speculative archaeology or the application of indigenous concepts to create alternative scenarios: In the setting of the former Dominican Church, visitors encounter female androids that communicate with transgenic maize plants, world-healing witches, and a glowing serpent woman whose light blinds spy drones.

Interdependence and mutual care are central to the worlds the artists have designed and act as counterpoints to appropriation, extractivism and exploitation.

Talks

What does the fight over a people’s land, past and worldview mean nowadays? Can technologies assist in decolonising history and culture, and in claiming climate justice? Which practices and methodologies, knowledges and experiences can help in shaping realities and futures beyond exploitation and dispossession?

Curated by Daphne Dragona, the EMAF 2021 Talks programme examines what ‘possession’ and ‘being possessed’ means in and for the contemporary world, exploring their interrelation. Speakers will discuss questions of property and control with regard to land, identity and information, while also looking into the power of beliefs, habits and dominant narratives. At the core of the programme lies the connection of today’s forms of extractivism and exploitation – be it natural resources, human power or data – to settler colonialism and racial capitalism. The talks will refer to the links between fossil fuel economies and colonial plantations, technoheritage and cultural dispossession, contemporary hidden workforce and slavery, digital habits and collective trauma. Invited theorists, artists and activists will address the enduring legacies of racism and toxicity, putting the emphasis on the ongoing fight of networks and ecologies of resistance. Paying attention to ancestral and contemporary technologies and cultural practices, the talks programme of EMAF 2021 underlines how different worlds still need to be acknowledged in order for this planet to be inhabited differently.

All talks are still freely available on our Vimeo channel.

Campus

The festival section EMAF Campus is once again offering a platform to classes and specialist groups from European academies and universities in this festival year. Due to Corona, these will feature for the most part on the streaming platform emaf.cinemalovers.de, but also on-site in Osnabrück in the windows of the hase 29 art space, in the windows of the Institut für Kunst|Kunstpädagogik /Institute for Art/Art Education in the Seminarstraße and in the window of the bbk art quarter.

The classes of Julika Rudelius from the Hochschule für Kunst /University of the Arts Bremen and Candice Breitz & Eli Cortiñas from the Hochschule für Bildende Kunst Braunschweig / Braunschweig University of Art will present installations and videos, while the class of Katarina Zdjelar from the Piet Zwart Institute, Rotterdam will be represented with a video programme. The Institute for Art|Art Education will also have videos from the modules of Bettina Bruder and Barbara Kaesbohrer in its programme and the Osnabrück University of Applied Sciences will offer apps and videos from the Media & Interaction Design course, supervised by Christoph Mett, Hannes Nehls, Björn Plutka und Michaela Ramm.

You can find the #Smalltalks of the students of the HBK Braunschweig, which were created in the context of the EMAF, on our Vimeo channel.

Specials

This year, attending perfomative events and taking an active part in the festival is no easy feat. The EMAF is therefore offering three special projects in line with the Corona measures.

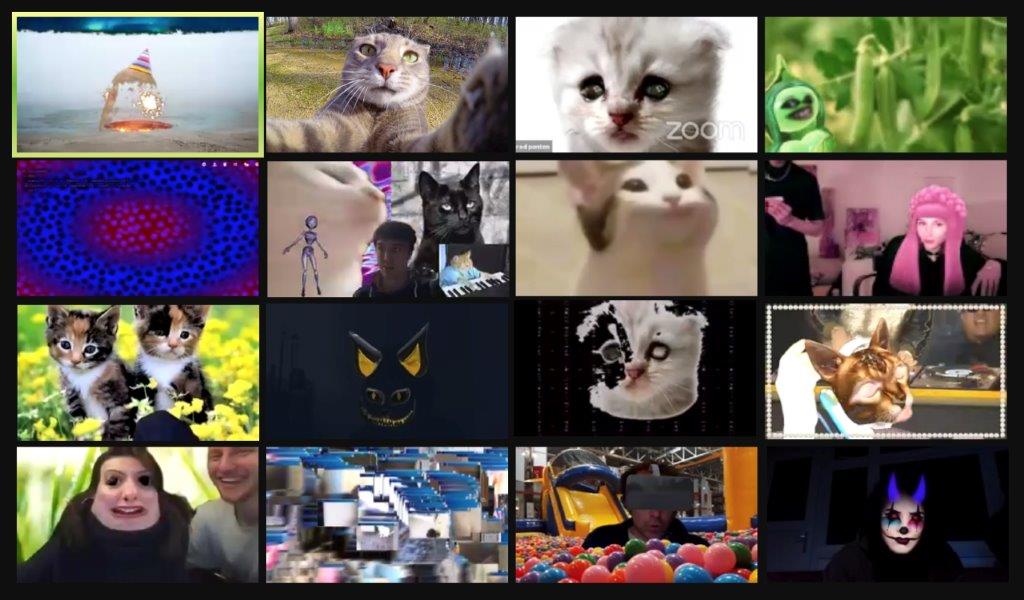

In collaboration with IMPAKT, the EMAF invites you to the Bal Masqué, a one-of-a-kind virtual party, on Saturday 24 April 2021. The Bal Masqué is a virtual club night and a Corona-proof combination of an online dance battle, a digital masked ball and any number of individual VJ sets. You are all invited to wear your craziest digital or real masks and party with us! If you prefer, you can join the party completely anonymously behind your mask, but you can also choose to take centre stage and join one of the battles that we will arrange during the Bal Masqué. The battles are the ball’s highlights, in which three participants at a time compete for the prize for the most amazing background and mask performance.

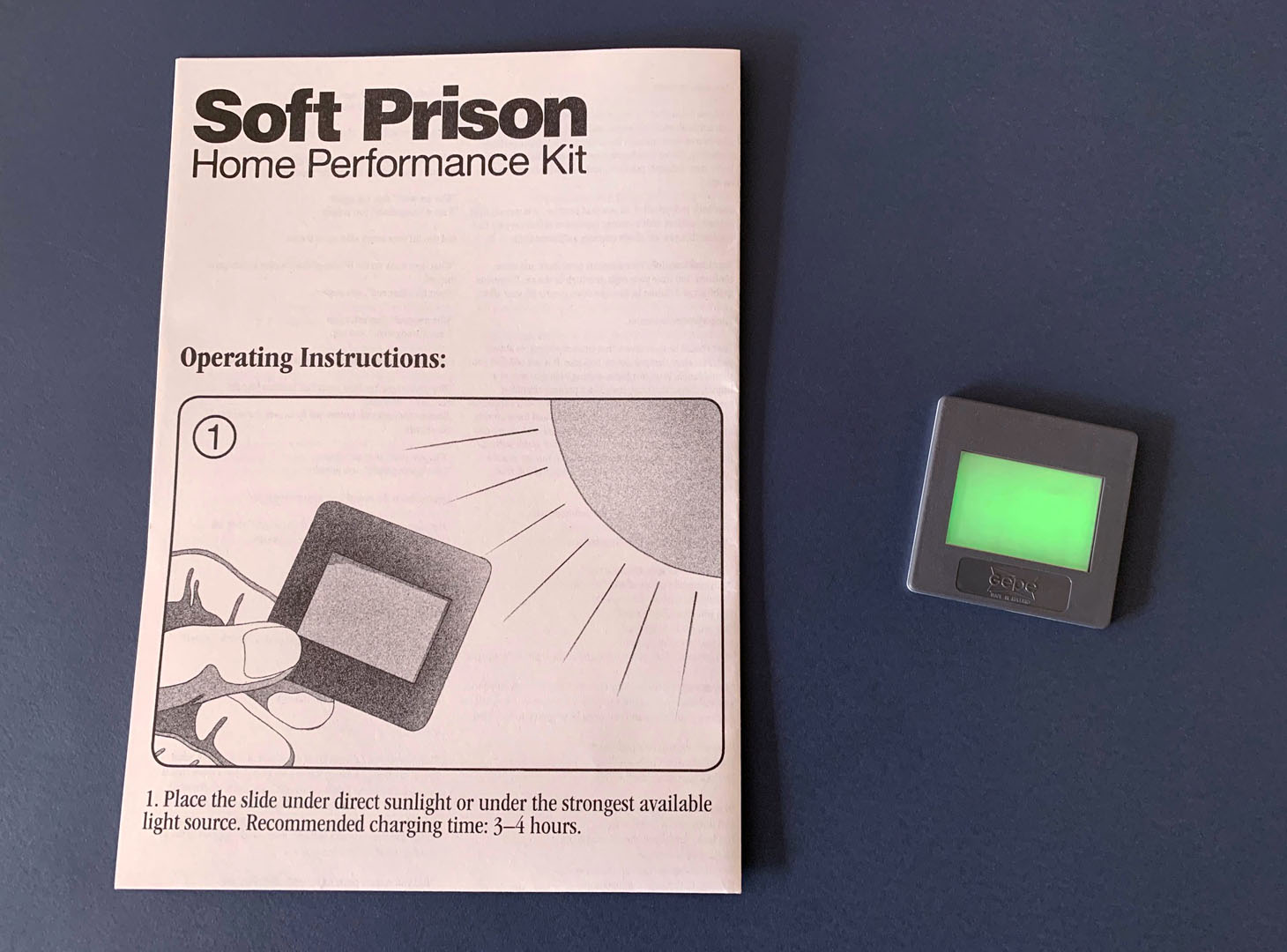

The home performance kit Soft Prison by the artist duo OJOBOCA offers an exceptional opportunity to be both performer and audience at the same time. “Along with our step-by-step instructions, a simple device will teach you the art of getting your body to create a completely different situation for you. Inside the box you’ll find everything you need to make yourself the ultimate performer of yourself”. OJOBOCA (Anja Dornieden & Juan David González Monroy)

My flesh is in tension, and I eat it is a joint Mail Art Project by the artists Teo Ala-Ruona and Jaakko Pallasvuo that references the film programme “The New Death“, curated by Steve Reinke and Jaakko Pallasvuo. “My flesh is in tension, and I eat it is a sexual love-letter to a swamp. It is a self-abandonment in textual form whose author dreams of complete submission to bodily decomposition.” (Teo Ala-Ruona and Jaakko Pallasvuo)